Flogging for criminals - throughout history

Flogging for criminals - throughout history

Adam Cohen, TIME

It’s tough stuff and generally considered a barbaric punishment that the 21st century Western world would and should never consider. That makes it a bit startling to find a new book by a serious U.S. academic arguing that the U.S. should start flogging criminals. Peter Moskos’ In Defense of Flogging might seem like a satire — akin to Jonathan Swift’s “A Modest Proposal,” an essay advocating the eating of children — but it is as serious as a wooden stick lashing into a blood-splattered backside.

Despite what you may think, Moskos is not pushing flogging as part of a “get tougher on criminals” campaign. In fact Moskos, who teaches at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, begins not by arguing that the justice system is too soft on criminals, but the opposite. So before you accuse him of advocating a cruel and unusual form of punishment, he offers this reminder: in the U.S., there are 2.3 million inmates incarcerated in barbaric conditions. American prisons are bleak and violent, and sexual assault is rampant.

And, Moskos points out, imprisonment is not just cruel — it is ineffective. The original idea for the penitentiary was that criminals would become penitent and turn away from their lives of crime. Today, prisons are criminogenic — they help train inmates in how to commit crimes on release.

Flogging, Moskos argues, is an appealing alternative. Why not give convicts a choice, he says: let them substitute flogging for imprisonment under a formula of two lashes for every year of their sentence.

There would, he says, be advantages all around. Convicts would be able to replace soul-crushing years behind bars with intense but short-lived physical pain. When the flogging was over, they could get on with their lives. For those who say flogging is too cruel, Moskos has a simple retort: it would only be imposed if the convicts themselves chose it.

At the same time, Moskos says, society would benefit. Under his proposal, the most dangerous criminals would not be eligible for flogging; the worst offenders, including serial killers and child molesters, would still be locked up and kept off the streets. But even so, he guesses the prison population could decline from 2.3 million to 300,000. That would free up much of the $60 billion or more the U.S. spends on prisons for more socially useful purposes.

(See TIME's photo-essay "Welcome to Prison Valley.")

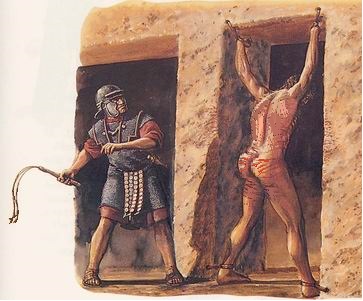

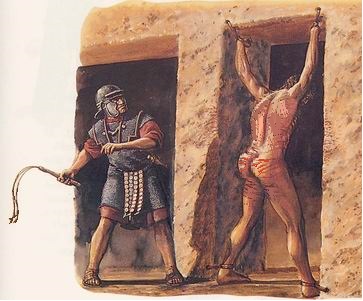

We associate flogging with authoritarian nations like Singapore and Malaysia. The practice, however, has deep roots in America. The "lash" was used brutally against slaves, of course, but common criminals were also flogged throughout the 1800s. And it took a long time to die out: as recently as 1952, Delaware administered 20 lashes to a convicted burglar.

Flogging could have more of a chance for a comeback than some might think. In fact, there could be a surprising amount of grass-roots support. In 1994, an American teenager named Michael Fay was famously convicted of spray-painting cars in Singapore and was flogged as part of his punishment. Fay's ordeal received intense media attention — the number of lashes was reduced from six to four after President Clinton appealed — much of it critical of Singapore. But as Moskos notes, a newspaper poll in Dayton, Ohio, where Fay's father lived, found that respondents supported the punishment by a 2-1 margin, and at a time of rising juvenile crime, many Americans seemed to echo that sentiment.

There would be legal issues, of course, but Moskos believes flogging would pass constitutional muster. He notes that the Supreme Court upheld corporal punishment in schools in 1977, rejecting a claim that it violated the Eighth Amendment bar on "cruel and unusual" punishment. Moskos also argues that the fact that convicts would be choosing it for themselves should remove the constitutional question.

Moskos insists there would be no "slippery slope," that flogging would not lead to amputations or stonings of criminals. But once we make inflicting pain on people an option, it seems likely or at least possible that states and localities would come up with their own ghoulish variations. Not long ago, another academic wrote a book arguing that we should use electric shocks to punish criminals.

(See a video on how yoga can help California's prisons.)

As for the remedy that most legal observers are pushing for rather than flogging — i.e., making our current prisons less barbaric — Moskos is dismissive of that happening anytime soon. Certainly the federal and state governments could focus on reducing overcrowding and violence in prisons, putting in place effective drug treatment and educational programs, and getting serious about alternatives to incarceration and helping prisoners re-enter society when they are released. But, in the eyes of Moskos: "Prison reformers — and I wish them well — tinker at the edges of a massive failed system."

Reading In Defense of Flogging is a lot like reading Woody Allen's classic "My Speech to the Graduates," in which he declares, "More than at any other time in history, mankind faces a crossroads. One path leads to despair and utter hopelessness. The other, to total extinction. Let us pray we have the wisdom to choose correctly."

Moskos would have us believe that there are only two alternatives for dealing with crime: the prolonged cruelty of incarceration or the briefer but more intense cruelty of flogging. But there has to be another way, doesn't there?

Cohen, a former TIME writer and a former member of the New York Times editorial board, is a lawyer who teaches at Yale Law School. Case Study, his legal column for TIME.com, appears every Monday.

Michael Jacobson

As states strive to get the best possible returns on their spending, it is important to know the total price of policy choices—in order to use prison resources judiciously and to rely on incarceration only when necessary to protect public safety.

According to a new report by the Vera Institute of Justice, prison costs that fall outside state corrections budgets are substantial. In many states these costs include fringe benefits, pensions, and retiree health care benefits for corrections employees (and the underfunded portion of these benefits in states that do not fully fund their annual payments).

Although in 2010 it cost more than $31,000 to keep someone in prison for a year, the study also found a wide range in the cost of imprisonment: from $14,603 per inmate in Kentucky to $60,076 in New York. But a state’s per-inmate cost has little to do with efficiency or effectiveness.

It is not necessarily a positive to have low per-inmate costs (as the result of overcrowding, for example) or a negative to have higher per-inmate costs (which may be due in part to interventions that help reduce recidivism).

The better goal is to be cost-effective: to spend resources wisely to get the best possible outcomes, both on an individual level for those who return to the community and, more broadly, as reflected by improved public safety.

Operating a safe, secure, humane and well-programmed prison is, and should be, an expensive proposition.

'Total Institutions’

Prisons are “total institutions” that provide everything necessary for inmates to live there—some for the rest of their lives. This includes adequate levels of security staff, food, treatment and programming (particularly those practices known to enhance staff and inmate safety and reduce recidivism), infrastructure maintenance, and appropriate health care for a population with significant levels of physical and mental illness.

Rather than focus on reducing per-inmate costs, the result of which may be poorer outcomes for security and recidivism, states should focus on limiting the use of prison for people who pose a real threat to public safety. Research tells us that continuing to increase the size of our prison systems will be only marginally effective at reducing crime.

We know, for instance, that targeted policing strategies, effective community-based reentry programs and increased high school graduation rates can improve public safety at far lower costs.

Declines in Prison Populations

We also see examples of states that have decreased their prison populations while simultaneously reducing violent crime. In New York and New Jersey, violent crime has declined dramatically at the same time that both states have relied less on the use of incarceration. From 1999 to 2009, the incidence of violent crime declined by 30% in New York and 19% in New Jersey, while going down by only fivev percent in the rest of the country.

At the same time, the prison population decreased by 18% in both New York and New Jersey after changes in policing and parole practices, as well as sentencing reform. In the rest of the U.S., , the prison population has increased by 18% during the same period. (In recent years, however, prison populations have declined in Maryland, Michigan, and Mississippi, while violent crime reached 10-year lows in all three states.)

It’s important to have an accurate picture of how much states spend on corrections.

This matters not only in terms of taxpayers’ dollars, but to ensure that our justice systems are effective and fair, and that society’s responses to crime reflect an offender’s risk to public safety. The question officials need to ask is not “How can we run a cheaper prison?” It is “How can we best use scarce resources to keep the public safe?”

In defense of torture - when it is right (justified)

Law and Order Michael Fay, style (Singapore)

A case for Corporal Punishment of criminals: Just & painful

Bring back flogging by Leo Savage (colonial style deterrence)

Paul's page - Corporal punishment considered (open discussion)

Islamic Traditionalism - sharia fundamentalism gets a bad rap

ALGOLAGNIA : the so-called joy-in-suffering ideal

The Meanest Mother in the Whole World - light-hearted poem

Both sides of the spanking debate (of children)

Punishment attire over the years

In defense of flogging adult offenders (Moskos)

Teaching an 'old dog' new tricks

Effectiveness: Flogging of Michael Fay

Home improvement: starting with yours truly

You've got to look at the eros dimension, also

Tough love may seem harsh, but it's meant to make a point

The ultimate purpose of discipline is teaching SELF-discipline

Flogging someone with a cane causes intense pain and permanent bodily damage. An Australian who was flogged for drug trafficking in Malaysia in the 1970s recalled that the cane “chewed hungrily through layers of” his “skin and soft tissue” and “left furrows” on him that were “bloody pulp.”

The High Cost of Prisons: Using Scarce Resources Wisely

It is no secret that prisons are expensive. Except for Medicaid, corrections is now the fastest-growing budget item for states. What may surprise taxpayers is that prisons are even more expensive than we thought, because of costs paid by state agencies outside of corrections departments.

Michael Jacobson is director of the Vera Institute of Justice. He is a former commissioner of the New York City Departments of Correction and Probation and a former deputy budget director for the City of New York. He welcomes reader’s comments

Corporal Alternative Sentencing

Why Judicial Corporal Punishment Beats Long Incarceration